2.1 Texture analysis

Existing literature lacks a definition and a comprehensive theoretical framework for orchestration. Recognizing this gap, this book embarks on a journey of exploration by posing the question, what if orchestration could be conceptualized as orchestration of something? Then orchestration will be the transformative processes applied to something in order to make it sound by instruments. While acknowledging the inherent problems of something, not showing any signs of orchestration or instrumentation, this upcoming chapter describes something as a texture, eventually refining it to a theoretical non-instrumental texture. Subsequently, Chapter 3 delineates the steps required to make a non-instrumental texture sound through instruments, whereas Chapter 4 examplifies what might be done to the non-instrumental texture through orchestration.

2.2 From transcription to reduction

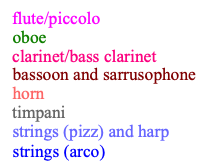

An example of orchestration as something being orchestrated could be the 2nd movement from Maurice Ravel’s Rapsodie Espagnole. Here, the orchestration is a new structure superimposed upon the original piece which was first written for two pianos. It does not include new material as such, but it does contain expansions and rearrangements of existing material (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Ravel’s Rapsodie Espagnole, 2nd movement. The three bottom staves contain a edited version of the original version for two pianos whereas the top three staves contain a edited version of Ravel’s own orchestral score of the same excerpt. Instruments are indicated using colors. As evident, no new textural elements have been added in the orchestral version, but some preexisting ones have been expanded.

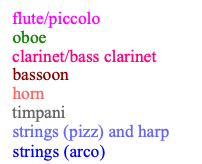

The example surgest orchestration to be viewed as a discrete set of transformations rendering the version for piano into orchestra or vice versa, as it happens in Ravel’s piano transcriptions of La Valse. An obvious objection to such a simplification would be that there are many, especially newer, works which feature playing techniques and musical material that are meaningless on a piano (e.g., circular breathing, microtonality, color trills, multiphonics, etc.), but also in order for orchestra music to become piano music, the music has to ajust to the possibilities and constraints of a piano. Transcription is adapting the music for a new medium no matter weather it is from piano to orchestra or from orchestra to piano. So, in order to see what is being orchestrated, one would have to see the music in an non-adapted version. A version with no instrumental adjustment. This is of couse implossible, but if an orchestration is an orchestration of something, this something should have no marks of instrumentation or orchestration. It could be thought of as the music with no specific instruments and no doublings, since this is the most obvious part of orchestration (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 6, 2nd movement. Above, an edited version of the original score containing all information of the original score. Below, a reduced version, where the orchestration in the form of doublings and instrument choices is omitted.

This reduced version could then be seen as a non-instrument-specific reduction, although one might argue that the music still maintains signs of instrumental idiomatics in the structure, phrasing, dynamics, and octave positions. Anyway, this is a game of thoughts, an impossible nullification in order to create an understanding of orchestration as something being orchestrated. The purpose of this reduction is to enable an investigation of how an underlying musical idea – represented by the reduced texture – is realized (i.e., orchestrated). This investigation will be carried out in chapter 3-4, what follows here is an examination of types of textures.

2.3 Texture types

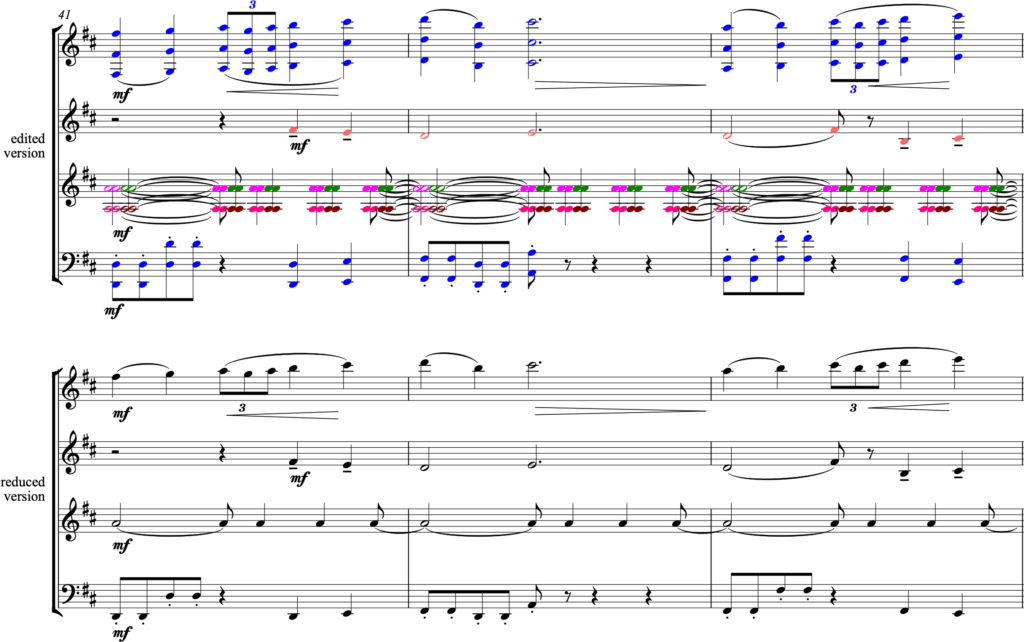

Textures are traditionally characterized as homophony, polyphony, melody with accompaniment etc. These terms implicitly subdivide textures into elements (melody, countermelody, accompaniment) or parts whose mutual relationship can be described as subordinate or coordinate.1 For example, we describe a polyphonic texture as consisting of independent voices, which can, at least in principle, be considered coordinate (i.e., equally important) . An accompaniment, on the other hand, is generally a companion to a melody and therefore can be described as subordinate. The classical texture terms, however, constitute a very limited set of texture types. They can therefore only be used to a limited extent on orchestral music. Figs 7–10 contain musical examples that in different ways are on the border of the classical types of textures.

Figure 7. Sciarrino’s 4 Adagi, 1st movement. A melody with an unrelated accompaniment.

Figure 7 could be described as a melody with an accompaniment, but the accompaniment is unusually stagnant and does not appear to adapt to the melody in any interpretable way. Is it then meaningful at all to claim that this “accompaniment” is subordinate to the melody?

Figure 8. Stravinsky’s Psalm Symphony, 1st movement. Co-occurring texture types (homophony and polyphony).

Figure 8 is made up of three functional elements, the top part of which is homophonic. The other two are separate melodic lines comprised of arpeggios and sequence motion. The complete texture could be characterized as a homophonic partial texture accompanied by an additional polyphonic one. Yet, the existing terminology does not offer any suitable means of describing the relationship between these two partial textures.

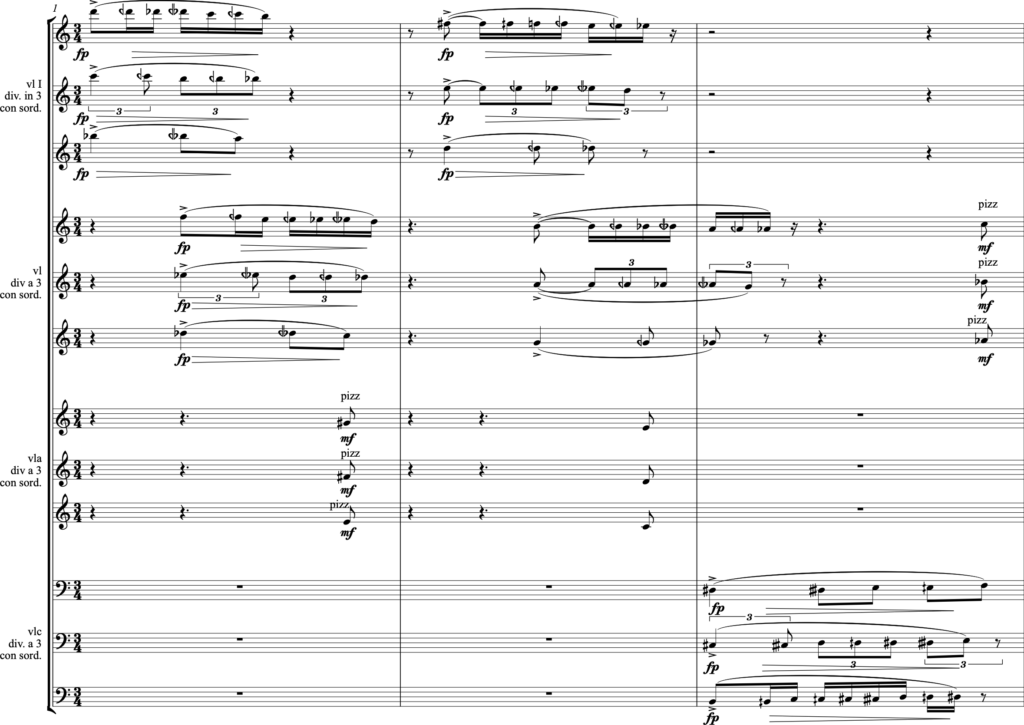

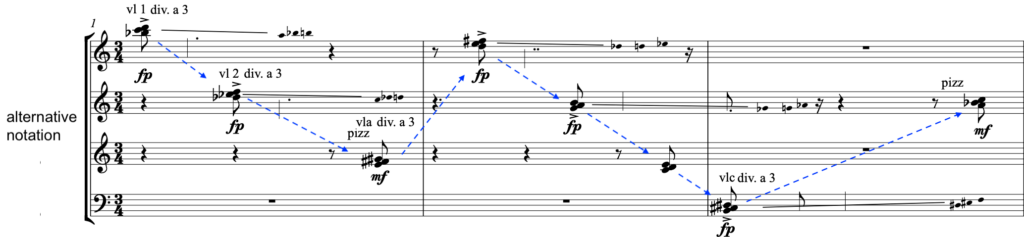

Figure 9. Lutoslawski’s Livre pour orchestre, 3rd movement, at top the original score and below the score in an alternative notation, showing the music as a cluster melody split between the strings, that is hard to characterize as either mono-, homo-, hetero-, or polyphonic.

In Lutoslawski’s Livre pour orchestre it is generally difficult to find anything that comes close to a traditional texture. An example is the beginning of the 3rd movement (Fig. 9), which could be interpreted as a form of cluster melody emerging across the four groups of string instruments. When this “melody” reoccurs a little later, it is accompanied by a countermelody in the bass, which occasionally features two simultaneous notes (Fig. 10), and a second (counter-)melody in the third measure.

Figure 10. Lutoslawski Livre pour orchestre, 3rd movement in an alternative notation. Two counter-melodies join the split cluster melody from Fig. 9.

Overall, Figure 10 could be regarded as a polyphonic fabric of three melodies. All of them are, however, very dissimilar and unusual, and none of them seems to accommodate one another. This makes it hard to describe their mutual relationship as one of sub- and superordinates.

The main problem resulting from using the classical texture types in the reading of the textures in Figs 7–10 pertains to unfulfilled expectations about how an individual textural element or part should behave and interact in relationship to the others. To solve this issue, the following section introduces two new types of textural elements.

2.4 Singular and compound elements

The two new types of elements – singular elements and compound elements – are defined by their structure. A singular element is an element of one note at a time whereas a compound element consists of multiple simultaneous notes.

A singular element can be a traditional melodic line, but it does not have to be either clearly melodic, musically prominent or in the foreground of the soundscape – it might even appear as pseudopolyphony.

A compound elements can be an accompaniment consisting of several superimposed figures, but they do not need to be discrete, harmony-based, subordinate, or positioned in the background of the soundscape. Usually a compound element get its identity from more general features such as contour, note density, or spatialization, while a singular element is typically more dependent on its specific pitch content and sequential order. None of the new two element types has a predefined position in the soundscape. Singular and compound elements can be combined into any possible constellation of subordinate and coordinate relationships, depending on each element’s character, activity level, volume etc.

A compound element could be seen as a sum of singular elements, as a chord could be seen as a sum of separate notes. But in both cases the sum is more than its constituent parts. Also when doubling a chord in a choral we only doubles specific notes of the chord, making a partial doubling. Similar in orchestration of a compound element a doublings is partial, whereas a doubling in a singular elements is a complete doubling. Finally, when talking about orchestration, singular elements can normally be played by one instrument alone, allowing a certain feeling of identity to an element, whereas a sum element usually requires the participation of several orchestral instruments.

If we look at Figs 7–10 again, they can now be described as such:

Figure 11. Sciarrino’s 4 Adagi, 1st movement. Two singular elements.

Figure 11 consists of two subordinate singular elements; they are adequately described as singular elements because both elements comprise only one note at a time and subordinate because the upper element is active and dynamically varied whereas the lower one is static and ppp.

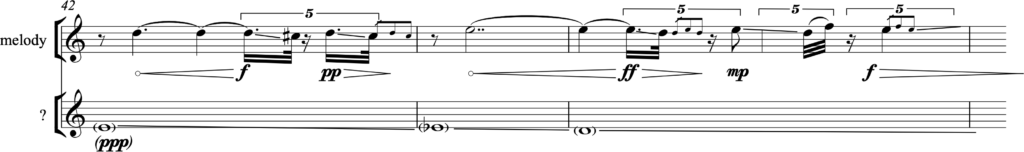

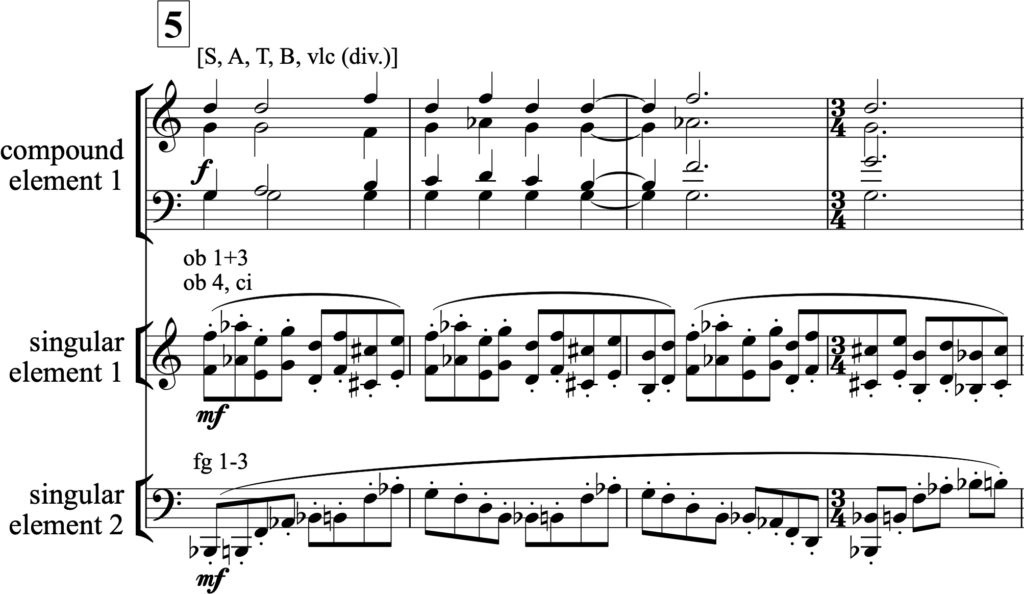

Figure 12. Stravinsky’s Psalm Symphony, 1st movement. One compound element and two singular elements.

Figure 12 consists of one dominant compound element (f) and two subordinate singular elements (mf).2 The two singular elements have largely the same intensity, dynamics, and activity level. Consequently, they are organized as mutually coordinate and subordinate to the dominating sum element.

Figure 13. Lutoslawski Livre pour orchestre, 3rd movement in an alternative notation.Three compound elements.

Figure 13 includes three compound elements, given that multiple notes occur simultaneously in all three elements. Compound element 1 is dominant via dynamics, placing the other two, albeit quite active, elements in the background. Elements 2 and 3 are mutually coordinate as they contain approximately the same activity level and (presumably) the same dynamics.3

2.5 Summary

In this chapter, a distinction has been made between orchestration and texture. In the texture analysis, all decisions pertaining to instruments and doublings are removed, and the music is described as a texture of elements. This can be either in the form of classical texture types like homophony, polyphony, heterophony etc., or as a combination of singular and compound elements. A singular element is an element that consists of one note at a time. A compound element is an element that consists of several simultaneous notes. Singular and compound elements can be combined freely as subordinated or coordinated or as a combination hereof, depending on their relative dynamics, character, and activity level.

1) Attention is drawn to the fact that the classical texture types rest on an unclear system in which a melody is defined structurally (e.g. one note at the time), an accompaniment is defined by its function, a fugue is characterized in terms of the number of voices, whereas a heterophonic texture is defined by the similarities of the composite parts. For a discussion of musical texture in a historical context, see J. Dunsby’s (1989) “Considerations of Texture”, Music & Letters, 70(1), 46–57. –>

2) Octave doublings are perceived as one part and, therefore, the middle staff is still a one element. More about doublings in Chapter 4 and about perception in Chapter 6. –>

3) Dynamics of element 3 are not indicated in the score. –>